http://host.madison.com/news/local/education/university/article_3f2b9556-f8d4-11e4-b6d5-73f4bf76cf8d.html

5/13/15 • By Pat Schneider

“It’s difficult. You are not guaranteed work, so you are livving under the fear of not having work.” — Michael McDaniel, a part-time instructor at MATC.

Michael McDaniel wrote “What was your first job?” on the board of a classroom at Madison Area Technical College. His students responded with brief accounts of their experiences, setting the stage for reading a story about a first job in “The House on Mango Street” by Sandra Cisneros.

Friendly and funny, McDaniel worked to help the 10 students identify themes in the coming of age novel about an immigrant girl in Chicago: the scary journey from home into the broader world, the tensions of differing expectations and their clash with reality.

Student Israel Ortiz, a native of Mexico, said he sought out the class after taking an online course with McDaniel.

“I figured it would be interesting to see Latino literature from a U.S. approach, but it was because he was a good teacher more than anything,” Ortiz said.

He always has thought of McDaniel as “professor,” Ortiz said, and was surprised to learn that McDaniel is a part-time instructor who does not know from one semester to the next which classes, if any, he will be teaching.

McDaniel earns less than $8,000 a semester teaching a three-course load, considered full time in academia.

“When you see the amount of time he puts into it …” Ortiz trailed off before adding that at least one other teacher at MATC had talked about his part-time status.

“They are giving full efforts, and not being compensated for it,” Ortiz said.

That’s the sentiment among many of the thousand-plus adjunct instructors who teach thousands of students in Madison, at MATC, the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Edgewood College.

The circumstances of these adjunct instructors differ from institution to institution. They may struggle to paste together a sufficient workload to make ends meet, teaching at multiple local institutions. Others earn a comfortable wage, but bristle at the better pay and greater job security given tenured faculty doing similar work. Some profess appreciation at being given the opportunity to bring their professional experience to the college classroom.

All say they love to teach.

…

The public’s idea of college instructors’ work lives is dramatically different from the reality, at technical colleges, private colleges and public research universities alike, says Mike Kent, a part-time lecturer at MATC since 2005 and president of the MATC Part-time Teachers’ Union.

“You’re much more likely to receive a course from a teaching assistant or someone hired as part-time instructor – who may not have a desk or a phone number – than you are to have a ‘professor,’” Kent said in his union’s cramped office at MATC’s Truax campus on the city’s east side.

Part-time instructors were teaching half the courses at MATC during a spike in enrollment in 2010-2011, as adults scrambled to re-train after layoffs during the Great Recession, but today teach 30 to 40 percent of classes, Kent said. That rate is reaching 80 percent at some institutions across the higher education spectrum, he said.

In 2013, 46.7 percent of teachers at four-year and two-year higher education institutions across the country were part-time instructional staff, and 14.3 percent were full-time, non-tenure track instructors, according to statistics compiled by the American Association of University Professors. The percentage of instructors greeting college students that year who were tenured professors or on track to become one was 20.4 percent, down from 45.1 percent in 1975.

At MATC, part-time teachers are paid a median $2,600 per three-credit semester class and get no health insurance coverage, Kent said. Full-time instructors, by comparison, earn an average of $92,000 a year, get health insurance and are members of the Wisconsin Retirement System, he said.

Part-timers have no private offices, little contact with colleagues teaching similar courses and many teach at multiple schools, “cobbling together a career, doing as much work as full-time professors for a tiny fraction of the pay,” Kent said. “Their car is their office as they go from campus to campus.”

Adjunct faculty are not given any assurances about which courses they will teach and may get three daytime courses one semester, one evening course the next and none the following semester, Kent said. This unpredictability makes it hard to find and keep other employment to supplement income, he said.

It also means high turnover, with about one-third of part-timers leaving every year, Kent said. And that means a succession of first-time teachers, which erodes the quality of instruction, he said.

For example, Kent taught business statistics for the first time this semester. He spent a lot of time developing the curriculum, he said, but not as much time as he would if he knew he would be teaching the course over a long period of time. And if Kent never teaches business statistics again, he and his students won’t get the benefit of content curated and approaches tested over time.

…

McDaniel said turnover among instructors discourages student retention because a connection with a supportive instructor helps students stay in school, especially at schools like MATC. He shares an office with other part-time instructors, he said, so often holds critical one-on-one sessions with students in the cafeteria or other common spaces scattered through MATC’s massive main building.

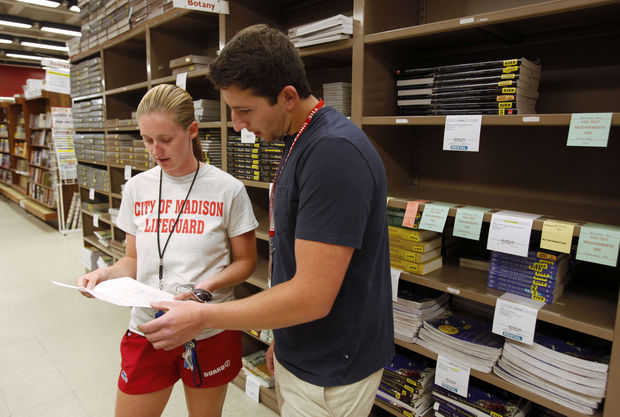

Michael McDaniel, a part-time instructor at MATC, teaches a U.S. Latino literature class at the college.

Teaching at MATC is challenging because the college’s policy of open enrollment results in classes that typically include students with a broad range of abilities. “Many are working a full-time job in addition to trying to be a full-time student, and all the socioeconomic issues plaguing the working class in the United States show up in the classroom,” McDaniel said. So, instruction must be tailored to students’ varied abilities, and interaction adapted to their multiple time constraints. Since most of his students say they want to transfer to four-year institutions, McDaniel says he tries to prepare them to survive and learn.

McDaniel taught three courses at MATC this past semester and hopes he will get three courses in the fall, but he can never be sure. He also will teach a single course this summer.

He estimates he works 60 hours a week for the three courses he is teaching, plus an additional 20 to 30 hours a week for additional functions at the college, in the writing center and as a facilitator for an internal problem solving program.

“It’s difficult,” he said. “You are not guaranteed work, so you are living under the fear of not having work.”

McDaniel, 49, got a master’s degree from Cornell University and completed all but the dissertation towards a Ph.D. in the English department, American Indian Program. He taught in the California state university and community college systems and at the Indian Community School of Milwaukee. He started teaching American Indian literature and English composition at MATC three years ago, and has since added U.S. Latino Literature.

“As an adjunct, you don’t say no,” he said. “You take whatever classes are available.”

To earn more money, he taught a course for the first time this past semester at the UW-Madison’s Wisconsin School of Business, where he was paid more than twice MATC’s course rate.

Although he has not applied for public aid other than subsidies for health care under the Affordable Care Act, McDaniel said he was eligible for food stamps until he got the contract to teach at UW-Madison and would become eligible again if he loses work at either institution.

“Any individual working as an adjunct must learn to live with economic insecurity,” he said.

McDaniel said he would like to dedicate all his time to students at MATC, but “unfortunately, due to economic conditions and institutional inertia, I must navigate the market forces of higher education,” he said.

…

The market forces of higher education have pushed compensation for adjunct college instructors so low that they are a target for SEIU, a national labor union best known of late for its “Fight for $15” campaign among fast food workers that seeks to raise pay to $15 an hour. The campaign among adjuncts has set a goal of $15,000 per academic course taught. That’s an aspirational goal as much as a practical one, activists say. But they hope it ignites a conversation about how much money spent at colleges is spent on classroom instruction.

MATC’s part-time teacher’s union, Local 6100 of the American Federation of Teachers-Wisconsin, has re-certified twice since the 2011 enactment of Gov. Scott Walker’s Act 10, which gutted the power of public employee unions.

Collective bargaining for public employees now is restricted under state law to increases in pay tied to inflation, but Kent said he is hopeful of improving conditions under a shared governance model introduced by Jack Daniels, who became MATC president in 2013.

Daniels said compensation – pay and working conditions – is the focus of shared governance councils that will develop proposals to be brought to him for his recommendation to the college’s board of trustees. The college, meanwhile, has been cutting expenses to avoid a shortfall in its operating budget for next year.

He was not hopeful about offering adjuncts guarantees in what courses they will teach.

“Adjuncts across the country aren’t guaranteed jobs – they teach based on need,” Daniels said. “But I don’t know of any college institution that could function well without adjuncts. They are a vital segment of our employee base and we’re looking for ways to improve their working conditions.”

One change might be in the way part-time and full-time statuses are defined, he said.

…

The number of instructional staff, as opposed to faculty, has risen sharply at UW-Madison over the past 25 years, mirroring a national trend. Today there are nearly as many instructional academic staff teaching students as there are faculty members, not to mention the graduate student teaching assistants who work with faculty and can be an undergraduate’s closest point of contact.

In 2014, there were 1,762 instructional academic staff at UW-Madison, compared to 2,085 faculty members, according to UW-Madison’s office of Academic Planning and Institutional Research. Instructional staff was up 20 percent from a decade ago and more than 160 percent from 25 years ago. The number of faculty in contrast, has dropped by just over 5 percent since 1989, inching up some 1.5 percent in the last decade.

The university also employs many additional academic staff who conduct research, perform administrative tasks and fulfill functions other than course instruction under a variety of titles.

Hiring academic staff instead of faculty is a way to keep costs down, said Scott Mellor, a distinguished lecturer in Scandinavian studies.

“We are cheaper than faculty, and that can be a problem,” he said.

Mellor holds the highest rank in UW-Madison’s complicated system of instructional staff classifications. His job carries a salary that, at minimum, must be 85 percent of a professor’s minimum salary under university policy, he said.

The average lecturer in my department makes $55,000, and the average professor closer to $90,000. … I see how that is a problem keeping talented people, and it concerns me deeply.” — Scott Mellor, lecturer in Scandinavian studies at UW-Madison

Mellor has a Ph.D. from UW-Madison in advanced folklore studies and has taught as a lecturer there since 1999. He worked his way up through the levels of lecturer and senior lecturer and was made distinguished lecturer in 2009 in a merit selection process that looks a lot like what is required to get tenure, he said.

Instructional staff start work at the university with no job security, and may be hired to teach a course on a semester-to-semester basis. Campus policy prohibits staff from teaching in the same department for more than three successive years on that basis, however. Many staff members then are contracted to work on a fixed-term renewable basis. Some get “rolling horizon” appointments that run one, two or three years and require prescribed periods of notice if they are not renewed.

Mellor started on a staff, rather than faculty, track because his spouse was a faculty member and the university had not yet developed its policy of accommodating employment of two-faculty couples, he said. And educational backgrounds between instructional staff and faculty are typically very similar, he said. Instructional staff are not required to conduct research, as tenured faculty are, he said. Some do, however.

His online resume lists books, articles, conference presentations and invited lectures, yet after 16 years on staff he earns a few thousand more than the $50,736 minimum for academic staff of his rank. That is a common circumstance for instructional staff, but faculty don’t linger so near the bottom of the pay range, he said.

“The average lecturer in my department makes $55,000, and the average professor is closer to $90, 000,” Mellor said.

Full-time instructional staff at UW-Madison get the same health care and pension benefits as faculty.

The relationship between faculty and academic staff varies among departments, Mellor said, but it is quite collegial in his, with academic staff having a voice in many departmental policy deliberations. Mellor is concerned, however, that as the number of instructional staff rises on campus, he has begun to hear complaints about being underpaid.

“I see how that is a problem keeping talented people, and it concerns me deeply,” he said.

An instructional staff member in languages at UW-Madison, who did not want to be identified, said she is facing stalled pay increases and that staff is not well respected or consulted on major decisions in her department.

Staff are treated as lower-class citizens, she said.

Faculty get preference in course assignments, including summer school, a potential source of extra income, she said.

“Most faculty don’t need to teach over the summer; they should give consideration to others making half as much as they do.”

She would move on to another institution, but the job market is bad in her field, she said, and starting on a tenure track now would mean a cut in pay for several years.

A lecturer in the College of Letters and Science said he was grateful to professors for helping him get a job at UW, but that pay for lower-ranked teaching staff is “exploitative.” Lecturers by policy must be paid 75 percent of a tenure-track instructor of the same level, but many have less than full-time appointments, which sharply cuts their earnings.

“I don’t think it’s ethical at all, the pay scale is ludicrous,” said the lecturer, who asked that his name not be used. “We’re constantly in limbo, trying to leverage ourselves. It’s an incredibly precarious position.”

Mellor credited Chancellor Rebecca Blank with using a “critical compensation fund” to fill some of the more obvious pay gaps, but some $90 million cuts looming for the campus in Gov. Scott Walker’s budget next year likely will make further progress there impossible, he said. Staff members, under the terms of their employment, are much more vulnerable to layoffs, he said.

“But when you look at the economic reality of the country, there are a lot of people a lot worse off,” he said. And Mellor is hopeful policy changes to improve the lot of university staff can be made under a new human resources system, independent from the state’s system, that goes into effect on July 1.

Karl Scholz, dean of the College of Letters and Science, said UW-Madison doesn’t exploit its staff.

“In the higher education press, you see all sorts of articles about the exploitative relationships between folks poorly compensated teaching and universities and colleges leveraging that to cut corners. I don’t think that happens at UW-Madison and I don’t think it will happen for the foreseeable future,” he said.

The phenomenon in urban areas where a Ph.D. strings together four or five jobs at different universities is not a model that characterizes the commitment to providing a high quality education that guides his college, he said.

“I don’t think stringing together jobs to make ends meet is good for the person or good for the students,” he said.

What’s more, the Madison area doesn’t have enough higher education institutions to make that scenario likely, he said.

Instructional staff by and large is paid less than faculty, but they are not the only ones whose compensation is stalled, Scholz said. “It’s been a pretty lean decade.”

He said he is hopeful that the university’s new human resources system will offer great flexibility to address a number of job compensation and title issues. But increasing compensation across the university is a challenge, he said. “Our faculty salaries are well below our public university peers – our teaching assistant stipends are crazy low, compared to institutions we compete with for graduate students.”

Scholz said his college is working hard to mitigate the impact of coming budget cuts.

“I hope to avoid layoffs, and instead eliminate positions by not hiring to fill vacancies on both the staff and faculty sides,” he said. As of May 5, 92 vacant positions were cut in Letters and Science, including 48 faculty members and 18 academic staff. No layoffs had been scheduled.

…

Shad Wenzlaff was a traveling adjunct who focused on a single employer a few years ago to ease stress in his work life.

Wenzlaff had stopped work on a Ph.D. in art history at UW-Madison without completing his dissertation because he could no longer live on a teaching assistant’s stipend, he said.

“I don’t see how anybody at UW lives on TA’s income. And I had taken out some student loans, so of course I was in debt,” said Wenzlaff, 42. “I made the decision that I couldn’t live in the poverty neighborhood in Madison. I refused to do that.”

He recalled, at age 30, looking around at the relationship problems and social issues fellow graduate students were grappling with and concluding, “this is not a quality lifestyle.”

The decision not to complete his Ph.D. slammed some doors.

“I ended up being an adjunct who just floats,” Wenzlaff said.

He taught classes at several colleges in the region – three in a single semester at one point – until he decided he could no longer juggle courses, students and policies. Wenzlaff now teaches art history only at Edgewood College, where he also directs student research part time. The teaching and administrative functions together make him a full-time staff member and eligible for benefits.

Edgewood is a private, Catholic liberal arts college founded by Dominican sisters that espouses values like justice, compassion and community as part of its mission.

“Our values call us to do a number of things, and I think that is the basis of some of the things we have been doing the last few years” to improve conditions for adjunct faculty, said Dean Pribbenow, vice president for academic affairs at the college.

Edgewood has about 300 instructors, with just over 100 full-time tenure-track faculty, Pribbenow said. The number of part-time faculty varies, but in the fall 2014 semester, the college employed about 170 part-time adjunct faculty, he said.

Part-time faculty are used to teach some of the multiple sections of basic courses, but also to provide special expertise, especially in the college’s professional schools, Pribbenow said. On rare occasion, a “community lecturer” may be paired with an instructor of record to share their unique life experience, he said.

Pribbenow would not say how much adjuncts are paid, but said improving the experience of part-time instructors has been the focus of faculty committees. Over the past several years, the college has moved part-time faculty toward full-time teaching loads when possible and worked to promote them to more highly paid lecturer positions, he said.

“This is a national problem and we face the same challenges as many other institutions,” Pribbenow said. “We recognize it, we’re trying to do some things, and we know we have some room to go in that area.”

Wenzlaff said that as a senior lecturer, he has health insurance and retirement benefits and works in a positive culture.

“It’s the Dominican philosophy – it’s really beneficent,” he said. “I feel like I can respect what I’m doing at Edgewood.”

Wenzlaff supplements his income by teaching piano in his private studio. He enjoys being able to engage both his art and music talents, “but I wish I didn’t have to work so much,” he said.

…

Percy Brown, director of equity and student achievement for the Middleton Area School District, was an adjunct instructor for the first time this year in the School of Education at Edgewood, where he also is pursuing his doctoral degree.

“I provide a unique experience by being an African-American male in education,” said Brown, 41, who has a background in cultural competence training and grew up in Madison attending schools in the Madison Metropolitan School District. “To tell my success story and offer that lens is very useful.”

The students in one class last fall were all international students from Saudi Arabia, but those in other classes were nearly all white, Brown said. As the students train to teach in public schools where students are increasingly racially diverse, the college would do a disservice to them if it did not prepare them to meet the needs of those students, he said.

“I’ve received a lot of positive feedback for helping raise awareness of these issues before they walk into a classroom,” he said. “And it’s allowed Edgewood to diversify its staff.”

Brown comes from a family committed to social justice and that is a guiding influence in his life, so the compensation for teaching a college course or two goes beyond money and professional development, he said.

“I’m grateful to Edgewood College for calling on me,” Brown said.