-by Sarah Mosle, October 2016

“Substitute teaching has to be education’s toughest job. I’m a veteran teacher, and I won’t do it; it’s just too hard. The role magnifies the profession’s biggest challenges—the low pay, the insufficient time to plan, the ordeals of classroom management—into an experience that borders on soul-crushing. At the same time, the job drains teaching of its chief joy: sustained, meaningful relationships with students. Yet in 2014, some 623,000 Americans answered school districts’ early-morning calls to take on this daunting task. Improbably, among their ranks was Nicholson Baker.

Baker has written more than a dozen books, both fiction and nonfiction. Whether in pursuit of new material or because the economic plight of even acclaimed literary authors is more dismal than we knew (or both), he applied to be a sub in a “not-terribly-poor-but-hardly-rich school district” within driving distance of his home in Maine, where he lives with his wife. The criminal-background check sailed through, though you might wonder why a writer of novels so raunchy that he’s earned a reputation as a highbrow pornographer didn’t get any further vetting. Imagine the texted OMGs and weeping-laughter emoji had Baker’s students dipped into his notorious 1992 novel, Vox, an account of a man and woman having phone sex on a pay-per-minute chat line. (At one point, the guy runs into trouble xeroxing his penis for a co-worker he is trying to seduce—ah, the pre-sexting inconveniences!)

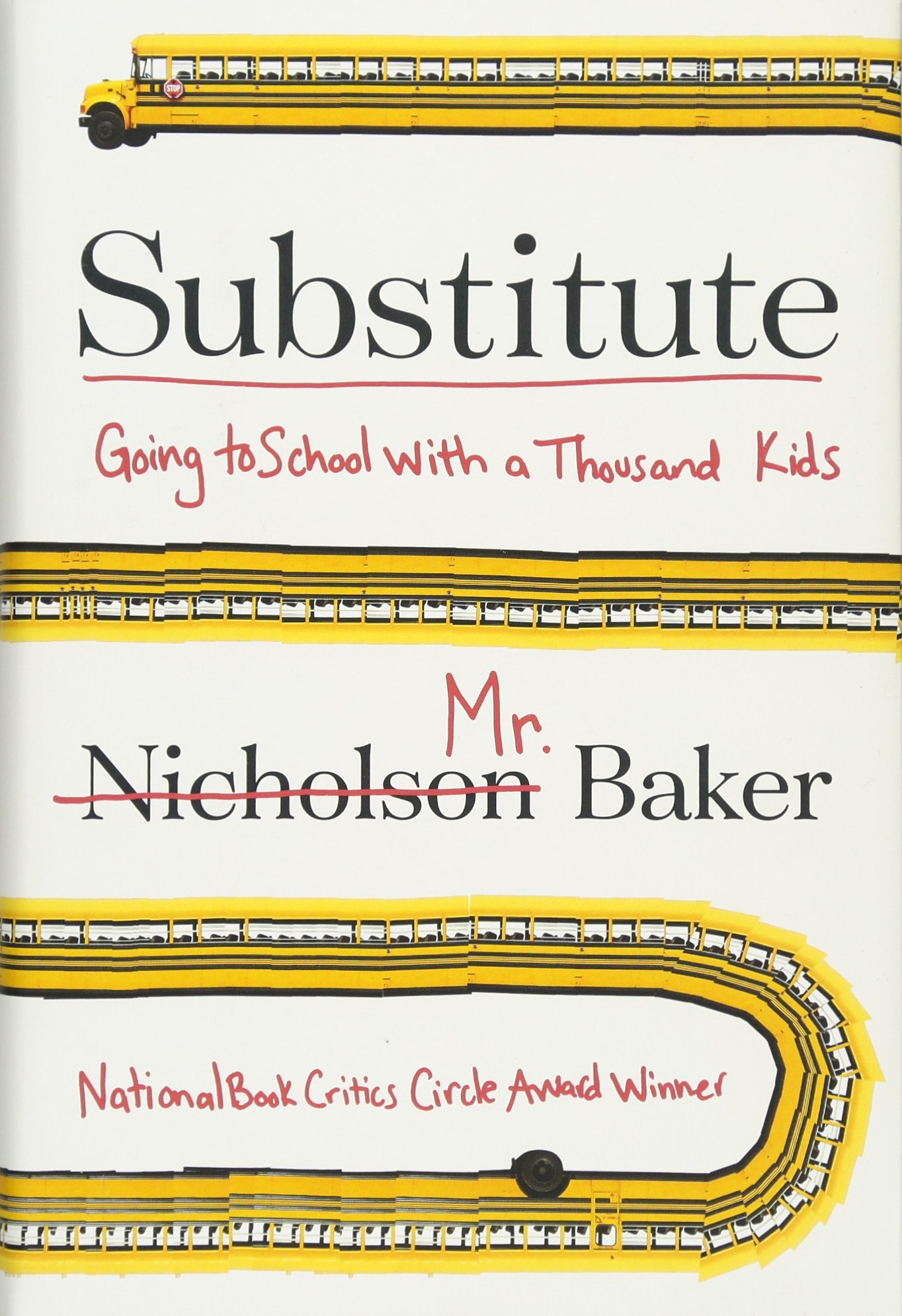

Baker calls the worst of the hectoring teachers “paid bullies.” At 700-plus pages, Substitute: Going to School With a Thousand Kids is a surprisingly hefty contribution to the life-of-a-teacher genre, especially given that Baker clocked only 28 days in the classroom—a place he’d love to liberate kids from. (He enjoyed a 1970s school-without-walls progressive education himself. ) Scattered across three months and six schools, grades K–12, each of those days is chronicled with the moment-by-moment vividness that Baker has made one of his trademarks. In his novel The Mezzanine, for example, he plumbs an office worker’s thoughts during an escalator ride; fireplace rituals receive punctilious attention in A Box of Matches. Well before his teaching stint has ended, Baker the substitute has shifted into saboteur mode—the reporter as mischief-maker.

Don’t mistake me, though, for a starchy pedagogue. I’m the first to appreciate Baker’s skill at doing what is too rarely done—and what his book convinced me all of us teachers should do at least once a year: follow a student through a whole hectic day in our own schools to soak up the experience. Baker often filled in for “ed techs,” aides who shadow students with special needs, so he was ideally positioned to get the kid’s-eye view. And the kids, in his telling, are mostly all right—funny, genial, and curious, even if exhausted. Start time for the middle and high schools in his district is an ungodly 7:30 a.m., and bus rides are long. How Baker kept all the students straight (a thousand names to learn!) while taking notes and juggling his official duties is beyond me—not that anyone could call him out on mistakes, since he uses pseudonyms throughout.

Baker describes a din sufficient to derail any train of thought: ceaseless PA announcements and interminable bongs between classes. (One school where I’ve taught replaced the bongs with classical music, a minor change with a major effect.) Teachers hector students constantly: “SIT UP STRAIGHT, EYES ON MRS. HEARN.” “IF I HEAR VOICES, YOU—OWE—RECESS!” Baker calls the worst of the yellers “paid bullies,” and he’s not at tough-love charter schools that swear by rigid discipline. He also captures the small silences, “those coincidental clearings in the verbal jungle.”

Baker transcribes the onslaught of acronyms, too: smile (Students Managing Information and Learning Everyday), fastt math (Fluency and Automaticity Through Systematic Teaching With Technology), smart goals (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely). The litany conveys the obvious: The proliferation of packaged pedagogical tools and rubrics is testimony not merely to the churn of reform interventions, but also to an enduring absence of actual reading, or much focused academic work of any kind. I will note that Baker doubtless saw a disproportionate share of vacuous handouts, from sites such as superteacherworksheets.com. Busywork is just about all that teachers suspect subs can manage, a view Baker confirms as he struggles to keep a lid on the classroom chaos.

School-issued iPads provide portals to websites—BrainPOP, Quizlet, Edmodo—that supply further distractions. You needn’t be a technophobe to conclude that the machines, which he describes being “put away in their cases and swung around like medieval maces,” are more trouble than they’re worth. Baker isn’t even in school very often, and he finds the internet connection constantly down or too slow to be of use. Kids forget passwords to online accounts or are locked out for other reasons. An attempt to repair a software glitch erases one student’s work entirely. The result is yet more interruptions and hectoring. Sometimes the iPads get confiscated unpredictably, sabotaging the teachers who haven’t given up trying to design tablet-based lessons. And of course, when the iPads are actually functioning, students are primarily playing games, watching YouTube, or listening to music on them. That doesn’t bother Baker at all, given what he considers the deadening alternatives on offer—and his own allergy to goody-goody obedience.

As the book progresses, that allergy intensifies. Baker lets his rebellious inner Rousseau loose in an environment that, as he repeatedly remarks, is notably short on men. (We encounter no more than a couple per building.) When one student in a high-school remedial literacy class mentions an assignment on Rousseau, Baker duly notes the French philosopher’s sexism. Rousseau’s ideas about education “only applied to men,” he explains to the class. “Women were supposed to serve and prepare and make everything, and then the men would be able to go wild and have a free existence.” Yet Baker is curiously deaf to his own rogue-to-the-rescue style as he warms up to the task of second-guessing the mostly female school staff that toils away in what he considers a killjoy fashion. All the while, of course, he can look forward to resuming his wild and free existence as a writer.

Baker’s idea of good teaching seems to be showering students with empty compliments. When eighth-graders show him drafts of their papers on a short story, his constructive criticism doesn’t extend much beyond exhorting them to “tell the truth.” Blithely challenging the diagnoses of students with special needs, he makes his credo clear: Stultifying school is always the culprit. At various points, he wonders why this or that child is taking medicine for ADHD when, in his snap judgment, the kids don’t need it. (How could he possibly know, given that he’s seeing them on medication?) In the most egregious example, he takes it upon himself—after just one class with a 12-year-old who Baker has been advised has “some issues with emotional stability”—to urge the boy to cut back on whatever drug he’s taking. In this case, Baker does finally bring his concerns to the nurse—the only time he does so in the book—and she’s in no need of his wisdom. She’s already completely on top of the situation.

Baker starts actively undermining school routines, encouraging one girl in a middle-school math lab to flout the protocol of signing out of class. He tells another girl in the same lab, which is for struggling students, that she might be better served by homeschooling. For students who aren’t academically inclined, he has concluded that vocational education is the answer—and brooks no dispute. Two high schoolers, one of whom has already revealed that he spent time in “juvie,” are in a metal-tech class when Baker loses his cool. They are goofing around, playing on an iPad, and then they lie about having completed their work. Baffled to discover the teens are as disengaged in this class as they have been in any other, Baker gets furious. “This is a fucking screen,” he says, pointing at the iPad—not the real, hands-on stuff he endorses. He berates the boys for refusing the path that he is sure is best for them.

So much for Baker’s indictment of bullying teachers—though he seems to make excuses for the men in the profession. “I liked Mr. Walsh,” he confides late in the book, even though his arrival features more all-caps yelling: “SHOULDER UP, ELBOW OUT.” “WE ARE GOING TO MOVE ON.” Now Baker doesn’t mind the raised voice, which he perceives as macho, like something you’d hear on a shop floor. “The only way he could survive as a middle school tech teacher,” Baker reasons, “was to develop a voice like a union activist’s and shout all talkers down.” Suddenly I had to wonder: How bad were the female teachers he’d witnessed yelling earlier? Were they truly over the top, or in Baker’s head, did women’s raised voices turn them into harridans?

Baker wishes his students could be happy and more carefree.

Baker, a specialist in fantasies, can’t resist indulging some pedagogical ones, too—of school days cut back from six hours to two; of only four or five kids per class; of “new, well-paid teachers who would otherwise be making cappuccinos” driving in “retrofitted school buses that moved like ice-cream trucks or bookmobiles from street to street, painted navy blue.” Just kidding, he sighs, offering a bizarre verdict on K–12 education. “Ah, but we couldn’t do any of that, of course,” he writes. “School isn’t actually about efficient teaching, it’s about free all-day babysitting while parents work.”

Which is not to say that Baker envisages more-serious work getting done in the school of his dreams. He keeps saying “I love these kids” and wishing they could just be happy and more carefree. Even 15- and 16-year-olds, in his view, are too young and sensitive to learn about the horrors of the Holocaust, or read The Things They Carried, about the Vietnam War. But loving students—especially adolescents—is exhausting, time-devouring, demanding work, rather like parenthood. That’s also why teaching can be so rewarding, not that Baker sticks around long enough to find out.

Whether Baker is aware of it or not, his sub’s perspective on some very average schools delivers a message Americans still need to hear: K–12 education, as the province of children and mostly women, regularly inspires panic, but all too rarely receives the serious, sustained attention it actually merits. It’s not just students who sink under an onslaught of obligations in school, with no moment to think or have an unhurried conversation or discover a new approach to a lesson. So do the adults who “serve and prepare and make everything,” to invoke Baker’s paraphrase of Rousseau. His book is a reminder that kids and teachers are often in the same boat, and both deserve better.