August 17, 2015 6:00 am • by Pat Schneider

UW-Madison student Kezia Weigel-Sterr was at University Book Store on the State Street Mall Wednesday to pick up the only text for the fall semester she was not able to rent online from a bookseller or publisher.

Her total textbook price tag: $286 — a lot less than the $400 or so she has paid in past semesters.

As a political science major, the books her instructors assign are not typically the big wallet busters used in some classes, particularly the sciences, but some courses require a lot of texts.

“There was one class last semester that had eight different books,” said Weigel-Sterr, who will be a sophomore in September.

She rented all those books and for another class used a reserve copy of the text at a university library instead of purchasing it.

“Nobody else was looking at it, but I could only have it out for two hours at a time,” she said.

For another course, her professor, Donald Downs, gave students a book he had written that was used as the text, Weigel-Sterr said.

Her story illustrates how college students are increasingly staying away from buying textbooks as a way to keep their spending down as the sticker price for books continue to soar, along with other college costs.

Textbook prices have climbed some 1,000 percent over the past four decades, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, with some titles now costing $400 or even $500. But students have been spending less on course materials in each of the past few years, according to a survey of the National Association of College Stores.

Students’ average annual spending on course materials dropped from $701 in 2007-2008 to $563 in 2014-15, according to the association.

The inclusion of non-renewable computer codes needed to access supplementary materials has driven up the price of some texts and obstructed the used-book market, said Patrick McGowan, president of University Book Store.

But student expenditures are nevertheless dropping because fewer books are being required as course materials, he said.

On the UW-Madison campus, instructors are increasingly using open educational material — notes, articles, and databases that either are available free on the internet or for which the university has purchased access, McGowan said. About 40 percent of courses being offered on campus this fall have no required books, he said.

That’s one reason that the most frequent visitors to the lower level of the book store — where the stacks of textbooks are located — were people in search of the public restroom on a recent weekday afternoon.

The other reason is that online registration for classes means that the crush to register and buy texts right before the start of the semester is a thing of the past. Students now have plenty of time to shop for the best price on their books and plenty of websites on which to do it.

For University Book Store it means that revenue from textbook sales is dropping “from the mid to high single digits” every year, said McGowan. But textbook sales and rentals still account for about half the revenue at the store, where the main floor focuses on the sale of Bucky Badger apparel and other items.

For many years, the university libraries did not purchase textbooks, but that has changed in the past decade, said university librarian Edward Van Gemert.

“Our observation is that more and more students are forgoing purchasing print textbooks,“ Van Gemert said. They may find ways to share the cost, and often postpone getting a textbook until it is clear it is actually required for a course, he said.

So the library has stepped in to provide access to some textbooks. For example, in 2013-14, the library spent $25,279 to purchase 538 course-related books and videos. A separate “high-cost textbook” fund of $4,000-$5000 a year buys multiple copies of particularly expensive books used in high-enrollment classes that are held on reserve at multiple libraries for two-hour loan.

Many instructors are helping students reduce course material expenses by seeking out open educational resources, said professor Kristopher Olds, chairman of the department of geography and a senior fellow in educational innovation.

Those materials — texts, podcasts, videos and other visualizations — are designed to be available digitally at low or no cost, Olds said.

UW-Madison is trying to get a handle on the development and use of such resources on campus, and will soon launch a study, he said.

The interest in open resources is spurred by an appreciation of the high cost of curriculum materials, a culture that says knowledge should be shared and technological innovation that facilitates sharing, Olds said.

Research also shows that ready access to curriculum materials, without obstacles of cost, enhances student engagement and outcomes, he said.

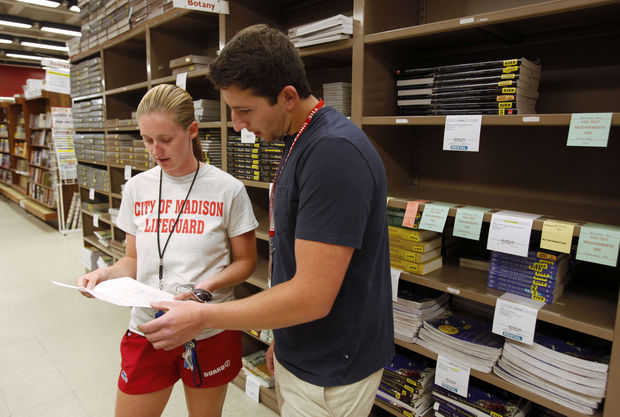

Instructors are sensitive to the cost of the materials they assign, said Alex Chase, a UW-Madison senior who works at the book store.

“Working here, I’ve been able to see that it’s a thin line they walk between giving students the best and latest information and the price,” said Chase, who is majoring in legal studies and political science and plans to go to law school.

And students network about how to keep the price of books down, said student Mariel Leering, also a book store employee.

“I belong to a sorority and I ask around for someone who has the book and can tell me if it’s really necessary,” Leering said. “And working here I’ve learned that the earlier you buy books, the likelier you are to find used ones. So I passed that along to my friends.”

She said everyone routinely shops websites like Amazon and Chegg for the best prices.

“It adds up,” she said. “If you save $5 on five textbooks, that’s $25.”

Leering, a junior, is studying genetics, a field where textbook prices can be high. But a friend is lending her a $150 textbook for one class this coming semester, leaving her to purchase only one $120 text and a couple of course packets of materials collected by the instructor.

Leering figures her course material expenses will total $150.

“For once, I’m not spending $400,” she said.

Not that she’d actually be paying that full $400. Her grandfather frequently buys some of her books and she has had a college fund since she was a child, Leering said.

“I was lucky,” she said, “hopefully I won’t be in too much debt when I’m done.”