https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/engineering-deans-response-bryan-caplans-case-against-don-weinkauf/?trackingId=4FsdBEUDqUphL%2FgGc2467g%3D%3D

“Each year as we suit up for college commencement, donning our regalia of fanciful robes, velvet berets and silk tassels, I make a point to interject to my colleagues the John Steinbeck quote from the Sea of Cortez, “it is a rule in paleontology that ornamentation… precedes extinction.” We certainly have major issues within our higher-ed organizations and ever growing threats in the education market. And in that light, I welcome provocative assessments of the current state of higher education. But in reading Bryan Caplan’s recent essay, What’s College Good For? (The Atlantic Jan/Feb 2018) previewing his pending book, “The Case Against Education,” I can honestly say that Caplan’s views will only metastasize our ills and accelerate any institution’s demise.

Caplan’s main thesis is that our higher ed system teaches only a minimal level of useful job skills, and as such, the value of a college degree, for the most part, comes from signaling one’s “pre-existing” traits to the job market. He estimates the mix of value at about 20% job skills and 80% traits. The pre-existing traits Caplan says one signals by attaining a college degree include: the ability to learn quickly and deeply, the commitment to working on something until it is finished, and the ability to adapt to new systems of management and work with others on teams. Caplan concludes that since higher education isn’t really responsible for the development of what would be viewed by most as highly desirable traits, and in the absence of any significant job skills training, that college “is a big waste of time and money.”

Completely missing from Caplan’s seemingly new revelation about poor job-skill training in college is the fact that the world renowned 4 year higher educational system that we have built in the U.S., from its dawn, has never endeavored to promote “job skill training.” Caplan’s estimate of 20 % job skills is about right (even for degrees as practical as engineering I would target about 30%), but the minimal influence that he claims education plays on the balance of the other critical traits is woefully inaccurate. Even with the 100 year plus tradition of teaching what Caplan describes as irrelevant subjects, there is little doubt about the role that U.S. higher-ed has played in inspiring our workforce to advance America’s political, cultural, technological and economic dominance over the past century. Higher-ed has thrived in discovery, fostered the synthesis of new ideas, and advanced both technological, medical, and social innovation at almost every level. And in the process, demanded of its students through its inherent pedagogical structure the repeated and rapid mastery of new subjects. And, yes, even mastery of subjects that Caplan finds “useless” and “irrelevant” like rhetoric, economics, history, and literature.

In the long term, employers care far less about the specific factual knowledge that a 22-year-old graduate brings to their company’s collective knowledge-base. But they do care about whether they have the humility and confidence to quickly learn something new and adapt to the incredible array of forces that are changing the landscape of their business at increasingly faster rates. And for outstanding employees, there is the expectation that they should be able to repeat this process of learning something new at a high level again, and again, throughout their careers. To me, this seems very much like the well-tested expectations of a college educational experience. It might be called the “knowledge” economy, but the reality is, it is the “ability to attain knowledge” economy.

During the course of a 4-year degree, a college student will engage-in and repeat the process of going from little-to-no knowledge in some subject and advance to some measureable level of mastery about 30 to 40 times. And by design, with each new course, the student has had to learn from someone new, in the midst of different groups of people, while needing to access different types of resources, under different sets of rules, and with increasingly difficult expectations of performance. The higher-ed calendar also provides ample time for meaningful internships and extra-curricular activities, like sports, student government, volunteerism, and study abroad, that bring real-world balance to an education.

Now, how much time we take to complete this transformation from high school graduate to adaptable learner, how much it costs, who we are serving, what teaching methods to employ, or how technology could improve this process are front-and-center of strategic planning at most universities. There is nothing sacred about the current 4-year college degree or structure. A four-year degree, as it stands today, with 130 credit hours and 40 different courses of high level learning involves about 4,000 to 5,000 hours of study. What various students do with that “practice” time is what brings distinction. But even with 5,000 hours of study, a college grad has merely walked along the shore of a great ocean of knowledge that humans have discovered in any subject. Some, like Caplan, would say “that they haven’t learned anything,” but others, like those that I work with, would say “that they know that they have a lot more to learn.” Students will benefit just as much from understanding the limits of their knowledge, as they will in drawing from the core.

As one might expect, everyone involved in Caplan’s higher-ed storyline is just in it for themselves. The big ruse called college he describes couldn’t be sustained without it. He is cynical about everyone around him. He is cynical about students (“the vast majority are philistines”), he is cynical about his fellow teachers (“the vast majority are uninspiring”), and he is cynical about the administration, “the deciders – the school officials who control what students study.” If I sensed the same level of self-interest that Caplan feels hanging over his academic environment, I would be equally disillusioned with higher-ed. But I don’t, so I am not.

Despite what some think, even in degree tracks viewed as practical as engineering, we do not engage in “job skill training.” In the St. Thomas School of Engineering, we promote and celebrate a 30% job skills / 70% traits balance that Caplan finds wasteful. I tell our students that there are no “Mechanical Engineer” jobs. However, there are incredible careers that can begin for those who have had the experience of learning the array of new subjects, from Philosophy to Thermodynamics, in our Mechanical Engineering curriculum. The products, the markets, the science, the customers, the designs, the finance, the regulations, the equipment, the timing, the documentation, the history, the communications, the manufacturability, the software, the laws, the cultures are so different for each company in each product sector, that we could not possibly “train” you for any specific job, because training you for one, would ill-prepare you for the vast majority of other possibilities. Let alone those that will emerge 4 years from now.

As engineering educators, the worse thing we could do for our students is to have them be surprised by what little they know as they walk through the door to their first job. Or, even worse, be over confident in what they think they know when they walk through the door of their first customer. And, in that light, the best thing we can do is to prepare them to walk into any new environment, fully knowing that you must first deeply listen, learn, question, understand, and as quickly as possible move to mastery. And then, plan on repeating that process again, and again, throughout their career. Much like they successfully demonstrated during their college education, regardless of the subject.

There are plenty of angles to constructively criticize and dramatically improve the current state of higher education, but the views in Caplan’s “What’s College Good For?” essay are no place to start.”

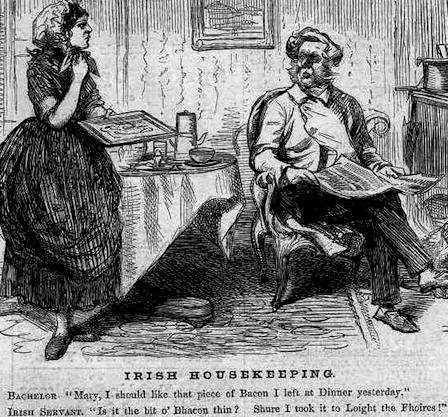

-A tenement interior as drawn in Harper’s Weekly.

-A tenement interior as drawn in Harper’s Weekly.